The potencial of Moscow's industrial zones - Russia

A Guest contribution by Tatiana Polidi, Executive Director of the Institute for Urban Economics, for the Moscow Urban Forum.

A few decades have passed since Moscow emerged on a post-industrial development path, leaving behind the zenith of production growth. The plants’ and factories’ vast territories are dispersed throughout Moscow resembling ugly patches, while residents of peripheral districts are forced to face a number of problems caused by the shortage of jobs close to their homes and the underdeveloped transportation infrastructure.

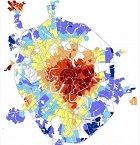

The drastic gap between the center and the periphery is one of the big issues modern day Moscow has to tackle. Developing a polycentric model by transforming industrial zones can become a valid solution for unloading the capital’s center without stretching the city boarders.

There are currently 209 industrial zones in Moscow occupying an area of 7.9 thousand ha or 16% of the city’s territory. If we count in the areas used for reloading and trafficking goods as well as engineering infrastructure, the total area would increase up to 15.5 thousand ha[i] (comparable to Paris’s area at 10.5 thousand ha), 478 ha of which are outside the industrial area borders. We (with my co-authors) attempted to estimate and analyze the perspectives of renovating the industrial zones in the framework of the interdisciplinary study titled Archaeology of the Periphery, prepared for Moscow Urban Forum.

The study showed the industrial zones have the potential to become future centers of a megacity’s life, stimulating job creation, emergence of parks and new residential areas. According to Moscow’s government, the situation leaves much to be desired. 24% of the industrial enterprises incur losses, depreciation of fixed assets is 47%. Only a third of all factories and plants are working efficiently.[ii] Most of the privately owned real estate in the industrial areas are not used for industrial production activity, but rather rented out as offices, warehouses and for other commercial purposes. Up to 40% of Moscow’s industrial zones are occupied be C-class offices, another 20% by car washes, services centers and so on and so forth. The remaining 40% are used for production and storage purposes.[iii].

The share of jobs in these areas easily proves low efficiency. 604,000 worked at manufacturing enterprises in 2011, which constitutes 9.3% of Moscow’s working population.[iv] At the same time, the average number of jobs in the central administrative district is 2.4 million.[v] This way, job density is 362.5 people per ha in the center, while this indicator is 13 less in industrial areas at 27.5 people per ha.

Increasing the efficiency of industrial zones by renovating them and shaping them into centers of gravity for job creation should become one of the central issues for Moscow’s urban planning policy, considering that global experience is valid proof of the effect such programs can have.

According to San Francisco’s urban planning department, industrial zones took up approximately 11.5 sq km or 14% of the city’s total area in the 70s. By 2000 the area decreased by almost 51% and was 5.9 sq km (5.8% of the city’s area), where 37% was taken up by office spaces and residential real estate. Current employment rate in the industrial sector is 11%, indicating a multi-fold increase in usage intensity.

France’s experience is also indicative of the trend – once WW II was over, the government launched a program for decentralizing the country’s industrial sector and relocating manufacturing enterprises outside the Paris agglomeration, most of which eventually found a new base in the suburbs. These operations resulted in a sharp decline in the share of industrial enterprises in Ile-de-France’s economy (down from 26% in 1954 to 15% in 1995). Out of the industrial plants that are now left in the city, the high tech ones prevail. The territories previously occupied by industrial zones are being used to develop the railway grid, which, in turn, contributes to the overall development of Ile-de-France’s transportation system. The remaining part is being used for the construction of multi-functional complexes and parks.

One of the examples of reorganizing a former industrial zone is a cultural eco-center project located in Seguin island south-east of Paris, which used to place the largest Renault plant with over 20,000 workers. A cultural eco-center project was proposed as a scenario for changing the territory’s image and raising its attractiveness. 25,000 sq m are now used for stores, offices and public spaces, including green and pedestrian areas. One of the key aspects of the reorganization is the construction of a large music complex with recording studios and performance venues, as well as a riverside arts center.

There are two radically different approaches to putting former industrial areas into new use. One entails a complete transformation into a residential area and the other – re-organization with mixed-use development for offices, innovation centers, industrial parks and retail infrastructure. As for Moscow, transforming the industrial zones between the Third Transportation ring and the Moscow Ring Road into residential area makes no sense from a balanced urban planning standpoint, since the area in question is historically overloaded with residential real estate affecting the quality of urban environment and aggravating the traffic situation.

A rational solution to the periphery’s problem would be using the industrial zones to create new commercial spaces including those for innovative production, as this would contribute to job creation and the improvement of quality characteristics of Moscow’s median area. The effectiveness of this strategy can be evaluated based on the first round of implemented projects – Flacon design-plant and ZIL Cultural Centre, Yuzhny port. Further involving the Moscow’s industrial zones into redevelopment process requires the new legal base – both federal and regional new legislation. These legal improvements will allow to eliminate the most of the investment risk, attract foreign investors and as a consequence to implement really interesting and useful spatial reforms in the city.

[i] According to data of the Unified Automated Information System of Moscow’s Unified Geographic Information Space.

[ii] Resolution of 24 February 2004, N 107-PP on the Targeted Programme for Reorganisation of Industrial Areas of the City of Moscow for the Period 2004-2006. Explanatory Note to the Programme.

[iii]http://clever-estate.ru/news/pressabout/ostanutsya-li-ofisyi-klassa-s-i-... (Russian language)

[iv] Federal State Statistics Service. Statistical Compilation on the Regions of Russia. Socio-Economic Indicators in 2011 http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/en/main/

[v] Strategy for the Socio-Economic Development of Moscow for the Period up to 2025.

Author: Tatiana Polidi is Executive Director of the Institute for Urban Economics

Based on Moscow Urban Forum research, co-authors Nadezhda Kosareva, Alexey Novikov, Aleksey Puzanov

Urbanplanet.info, 01/10/2014 by Christian Horn in Europe, Urbanism